By SUZANNE DOWNING

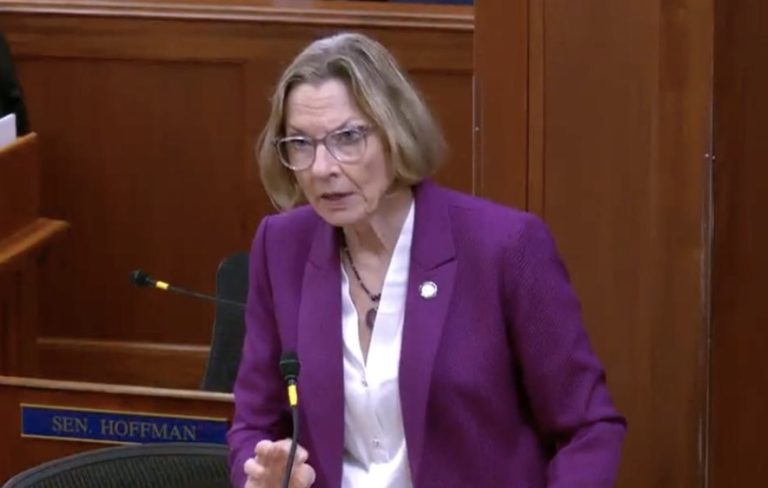

As the Alaska Legislature gavels in on Tuesday, we already know what’s coming: Oil taxes will be back on the table, with the usual suspects lining up to argue that Alaska just isn’t charging “enough.” Sen. Bill Wielechowski, Sen. Rob Yundt, Sen. Cathy Giessel, and the Democratic caucus have showed their cards before, and they’ll be back at the table again this session.

Before lawmakers convince themselves that higher taxes are a free lunch, they might want to look across the Atlantic at what just happened in the United Kingdom.

US oil producer Apache, no small player in oil and gas, has announced it will cease oil production at its assets in the North Sea by 2030. The reason is not geology, technology, or a lack of oil. It’s taxes.

Apache is not messing around; it has already suspended new drilling in the North Sea.

According to reporting by OilPrice.com, APA, Apache’s parent company, disclosed in a recent SEC filing that the UK’s so-called windfall tax, officially known as the Energy Profits Levy, has rendered continued production uneconomic. The levy is increasing to 38% from 35%. At the same time, the UK government is extending the tax’s expiration date to March 31, 2030, a year later than previously planned, and eliminating a 29% investment allowance that had partially offset the burden.

In plain English: Higher taxes, fewer incentives, and more uncertainty. The predictable result? Capital moves on.

Apache said its assessment showed that the expected returns no longer support the investments required under the combined impact of the tax and regulatory changes.

Apache entered the North Sea in 2003 after acquiring a 97% working interest in the Forties Field, one of the region’s major legacy assets. It has operated interests in the Beryl, Ness, Nevis, Nevis South, Skene, and Buckland fields, along with non-operated interests in Maclure and Nelson. This is exactly the kind of experienced producer governments usually say they want to keep. Instead, the UK taxed it out.

Since the windfall tax was first introduced during the energy crisis in 2022, operators in the North Sea have repeatedly warned that constant policy changes and rising taxes would drive investment elsewhere. Those warnings are now becoming reality. The irony, as OilPrice.com notes, is that reduced domestic investment will only increase the UK’s dependence on imported oil and gas, often from countries with weaker environmental standards and far less transparency.

That should sound familiar to Alaskans.

Alaska spent years in a cycle of tax instability that chased away capital, stalled investment, and contributed to declining throughput in TAPS. Only in recent years, following the passage of Senate Bill 21, has the state’s oil tax structure appeared relatively stable. Stability and predictability are key: Investors do not sink billions of dollars into long-term projects if the rules can be rewritten every legislative session.

There’s an old saying that lawmakers would do well to remember as the session heats up: If you want less of something, tax it. The UK just tested that theory, and the answer came back quickly and clearly.

Apache has had a footprint in Alaska for years, most recently in partnership with Santos-Oil Search on the North Slope, where the companies have successfully explored new wells.

As Alaska lawmakers debate oil taxes yet again, they should pay close attention. Alaska competes globally for capital. We are not owed investment. If we choose higher taxes and uncertainty, we should not be surprised when producers decide their money is better spent somewhere else.

Suzanne Downing is founder and editor of The Alaska Story and is a longtime Alaskan.

2 thoughts on “As Alaska’s Legislature gavels in, the UK’s oil tax cautionary tale shouldn’t be ignored”

Taxing old money and taxing the recycled money from what already was taxed isn’t going to make the state of Alaska richer like limiting governneny jobs/dependency and increasing resource development and private sector jobs

One day Alaskans general consensus will be they will get tired of being known as the backward state of doing everything backward when their backwardness has been causing us to run in circles and back up to correct mistakes. Eventually one gets tired of running around in circles.

Maybe it’s too late for productive Alaskans knowing as they do that their lobbyist-legislator team seem obsessed with sinking themselves and taking productive Alaskans’ lives down with them.

.

Could Alaska’s overtaxed oil companies and overtaxed residents have more in common with Venezuelans?

.

What if overtaxed oil companies and overtaxed residents believe, for good reason, they’ve run out of options as both realize honest elections and judicial integrity are things of the past, at least for a while? Both can, and are, going somewhere else, leaving the regime to figure out how to squeeze left-behinds for enough money to keep themselves, their lobbyists, their non-profit parasites, and their labor unions in business while Alaska’s economy goes to hell in a handbasket.

.

Corruption, incompetence, drugs, cartel violence, money laundering, inflation, election fraud, homelessness, human trafficking, illegal aliens, child abuse, child mutilation, child indoctrination, slums, violence against women, truancy, illiteracy, journalistic malpractice, authoritarian government, and contempt for the rule of law are problems in Venezuela too.

.

But now, for good reason, hope seems to be returning among Venezuelans. Oil companies are starting to run daily operations, albeit by phone and handwritten notes, while eight million expats make plans to return and rebuild the post-Maduro wreckage. Nobody believes things’ll be made right overnight, but optimism seems to be sprouting where there was none.

.

But, for no good reason, Alaska’s still mired in a morass of problems which only seem to be getting worse if state-sponsored media and public officials are to be belived and optimism …probably have to Google it to find any around here.

.

So it seems reasonable to ask what was the last straw, what led to the change in Venezuela, could something with similar consequences, like a twenty-first century Operation Greylord or an Operation Bid Rig happen in Alaska, especially if insiders and citizen journalists come forward with what they know?