On this day in 1955, fifty-five Alaskans gathered in Fairbanks to do something no other generation of Alaskans had ever done – write a constitution for a state that did not yet exist.

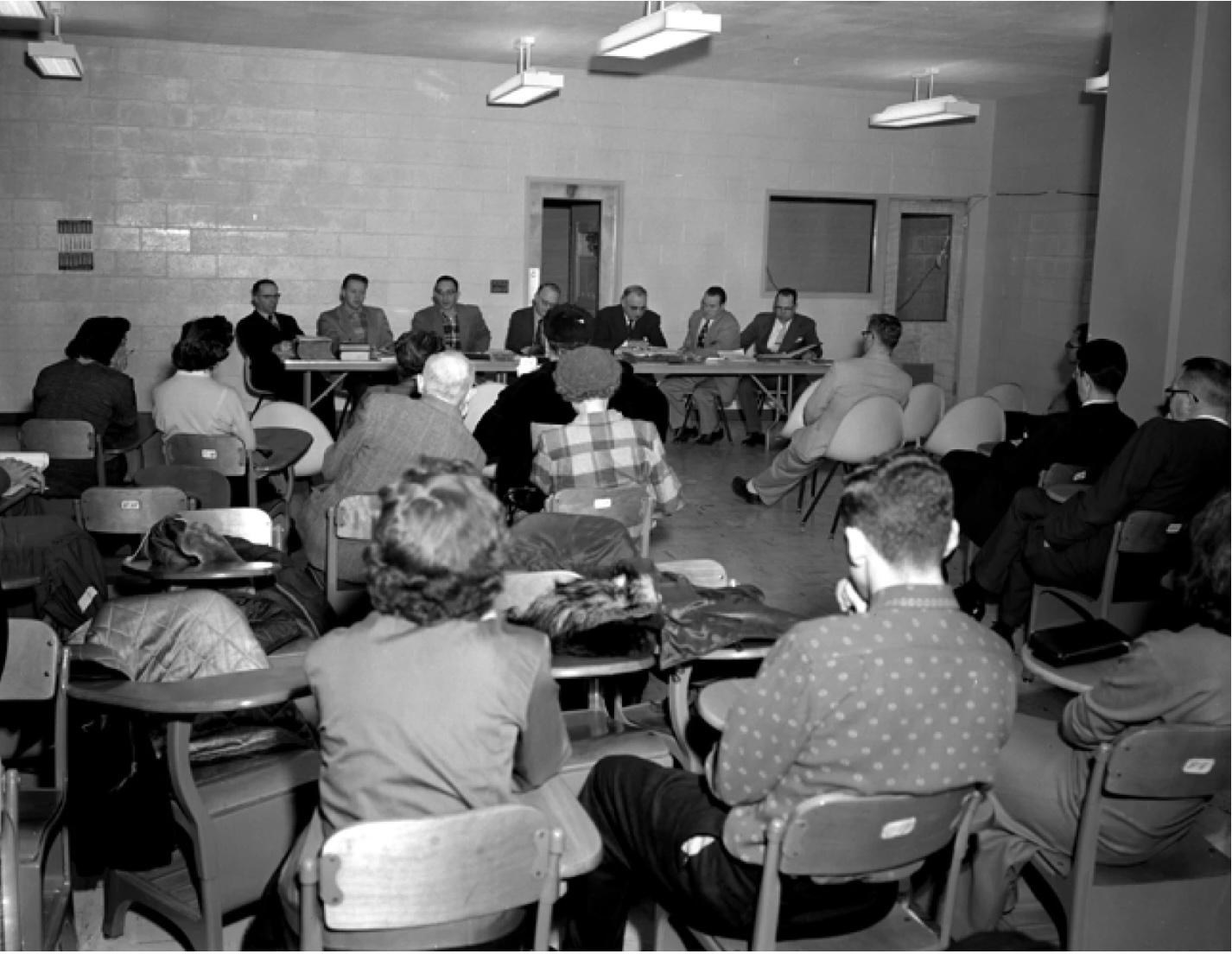

The Alaska Constitutional Convention convened on Nov. 8, 1955, inside the student union building on the University of Alaska campus in Fairbanks, now known as Constitution Hall. Over the next 75 days, through a dark and frigid winter, those delegates drafted one of the most admired state constitutions in the nation, and in the process, charted the path to statehood.

Fifty-five delegates were elected in a nonpartisan election held just two weeks earlier, on October 25, 1955. They came from every corner of Alaska, seven from each of the four judicial divisions, and 27 at-large. They were miners, lawyers, teachers, fishermen, homesteaders, and veterans. Among them were six women and two Alaska Native leaders, Frank Peratrovich of Klawock and James K. Huntington of Huslia.

William A. Egan, who would later become Alaska’s first governor, was chosen president of the convention. Other notable delegates included Ralph Rivers, Dorothy Awes Haaland, John B. Coghill, Victor Rivers, and Steve McCutcheon. Together, they represented the mosaic of a territory ready to govern itself.

The convention had been authorized by the Territorial Legislature earlier that year and funded with $300,000 — a bold investment in Alaska’s future at a time when statehood was far from guaranteed.

The delegates looked carefully at the constitutions of all 48 existing states and leaned heavily on the 1954 Model State Constitution produced by the National Municipal League. Their goal was clarity, brevity, and flexibility — a framework that would serve a vast and diverse land.

They succeeded. In just 75 days, the delegates produced a document of roughly 14,000 words in plain, modern English and finished faster than almost any other state constitution in US history. One delegate, R. E. Robertson, resigned in protest and did not sign the final document.

The Alaska Constitution broke new ground. It prohibited racial discrimination in public accommodations, gave strong powers to local governments, and enshrined the principle that Alaska’s natural resources must be managed “for the maximum benefit of its people.” That item has been argued mightily, as “maximum benefit” is an elastic term.

It’s far from a perfect document. Among its flaws is the sweeping ban on dedicated funds in Art. IX, §7. Almost every other state allows certain revenues (gas taxes, tobacco taxes, etc.) to be dedicated to specific purposes. Alaska prohibits this except for the Permanent Fund. The real-life impact is that every dollar goes into the General Fund and must be re-appropriated annually, leading to massive annual political fights.

In addition, it has one of the longest legislative sessions in the country (121 days), which leads to marathon sessions, and massive omnibus bills passed at 2 am.

When voters went to the polls on April 24, 1956, they approved the constitution by a two-to-one margin, 17,447 to 8,180. With that vote, Alaska declared itself ready for statehood.

To press their case in Washington, Alaskans followed what became known as the “Tennessee Plan,” electing two “shadow” senators and a representative to lobby Congress for admission to the Union. Their persistence paid off. Three years later, on Jan. 3, 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the proclamation making Alaska the 49th state.

The original constitution, signed on Feb. 5, 1956, is preserved today in a helium-filled case at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau.

One thought on “On This Day in Alaska History: Alaskans began to write its own future”

There were three tiers of districts from which delegates were elected. I think only four delegates were elected to territory-wide seats. Multiple people were elected from the territory-wide and each of the division-wide elections. The remaining delegates were elected from one or a combination of recording districts, which were used as a level of divisions below the judicial divisions in the 1910 through 1950 censuses (and largely formed the basis of early state legislative districts). Those districts elected only one delegate apiece. I’m to understand that Tommy Harris was elected from Valdez with only 150 votes. He had no intention of running, but was urged to do so when told that Bill Egan was going to run for a territory-wide seat. Also, Jimmy Huntington was not a delegate. I can’t think of who you may be confusing him with.